various feminist scholars have accused the Mbh of misogyny and of not expressing the female experience in depth, claims which i would heavily disagree with. i will unpack my arguments in further videos, but the angle that i want to present today is related to my previous video, in which i talked about how all perspectives are contained within the Mbh, and it itself states so. i would like to offer the perspective of the Mbh being a dialogue, which i learned while studying with Dr. Brian Black at Lancaster University during my postgraduate degree.

🌸 what kind of dialogue? between its characters, between different ways of life, different perspectives, between us, the audience, and the epic itself; it does not have an inherent opinion on the characters presented there: everything we learn is from someone’s perspective, either the narrator of a particular story, or the way characters relate to each other. so, are there misogynistic perspectives in the Mbh presented by certain characters? yes; as, similarly, there are misogynistic takes in the world today. the Mbh is more like a neutral observer, i would say; it does not uphold certain views, it merely documents them and invites you to contemplate them, absorb or challenge them.

because dialogue relies on context, it is very important to understand the context of an event in question to understand its nuances.

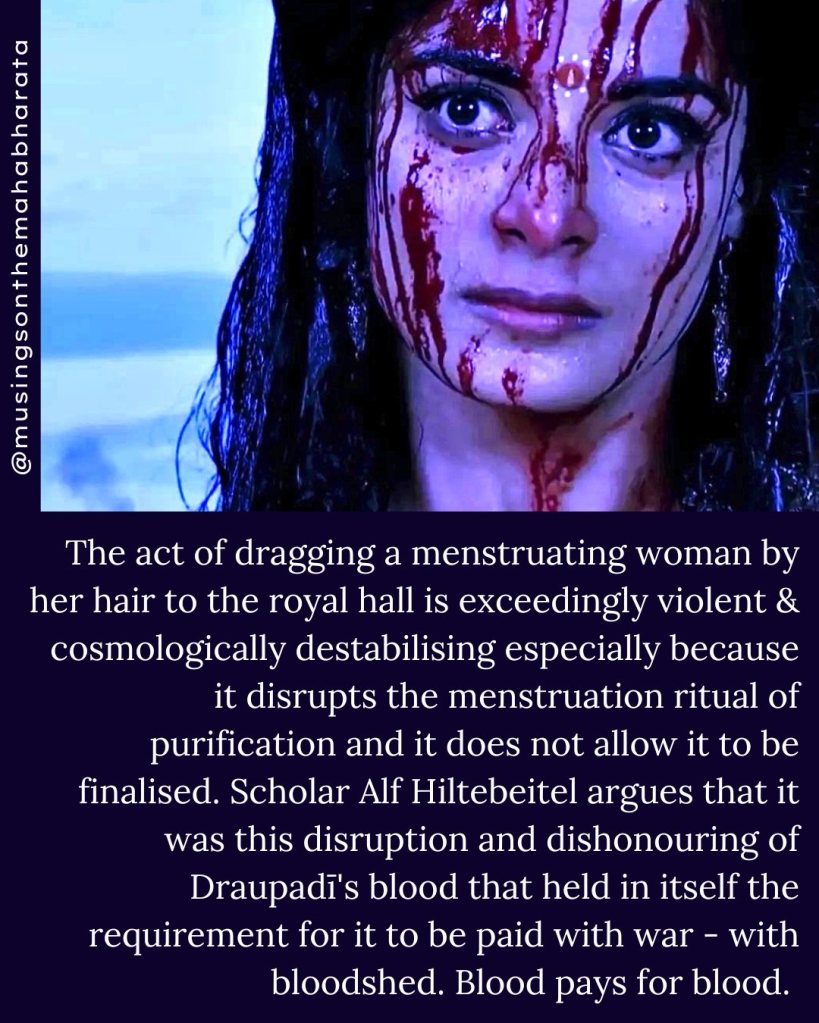

to demonstrate this, i will use an episode from the Mbh in which Yudhiṣṭhira expresses a misogynistic comment. this happens in the 13th parva; in a conversation with Bhīṣma, Yudhiṣṭhira asks him in an exasperated manner, why are women so deceitful and hard to please? (13.39) context: the war ends, and Draupadī’s sons are unlawfully slaughtered during a night raid. Yudhiṣṭhira faints when he hears the news of his dead son and nephews, then asks Nakula to bring Draupadī to the camp, lamenting that yet another sorrow would fall upon his beloved. Nakula brings a grieving Draupadī, who lashes out at Yudhiṣṭhira and aggressively congratulates him on winning the war and on becoming emperor, the undertone of this being: at what cost? (10.11) additionally, Yudhiṣṭhira is hit by a revelation from Kuntī, his mother, which greatly disturbs him; later on, an exasperated Yudhiṣṭhira asks this question to Bhīṣma.

now, is Yudhiṣṭhira misogynistic? i would say no; in fact, he later praises Draupadī’s merits and speaks highly of other women. is this contradictory? i would also say no; i think this episode showcases a very humane moment between two characters found in a moment of crisis, in which their children were murdered, and they express their pain by lashing out irrationally. in my view, it showcases how messy and multifaceted we are as humans, which, for me, is one of the great beauties of the Mbh. 💗

pt. 2: on authorship

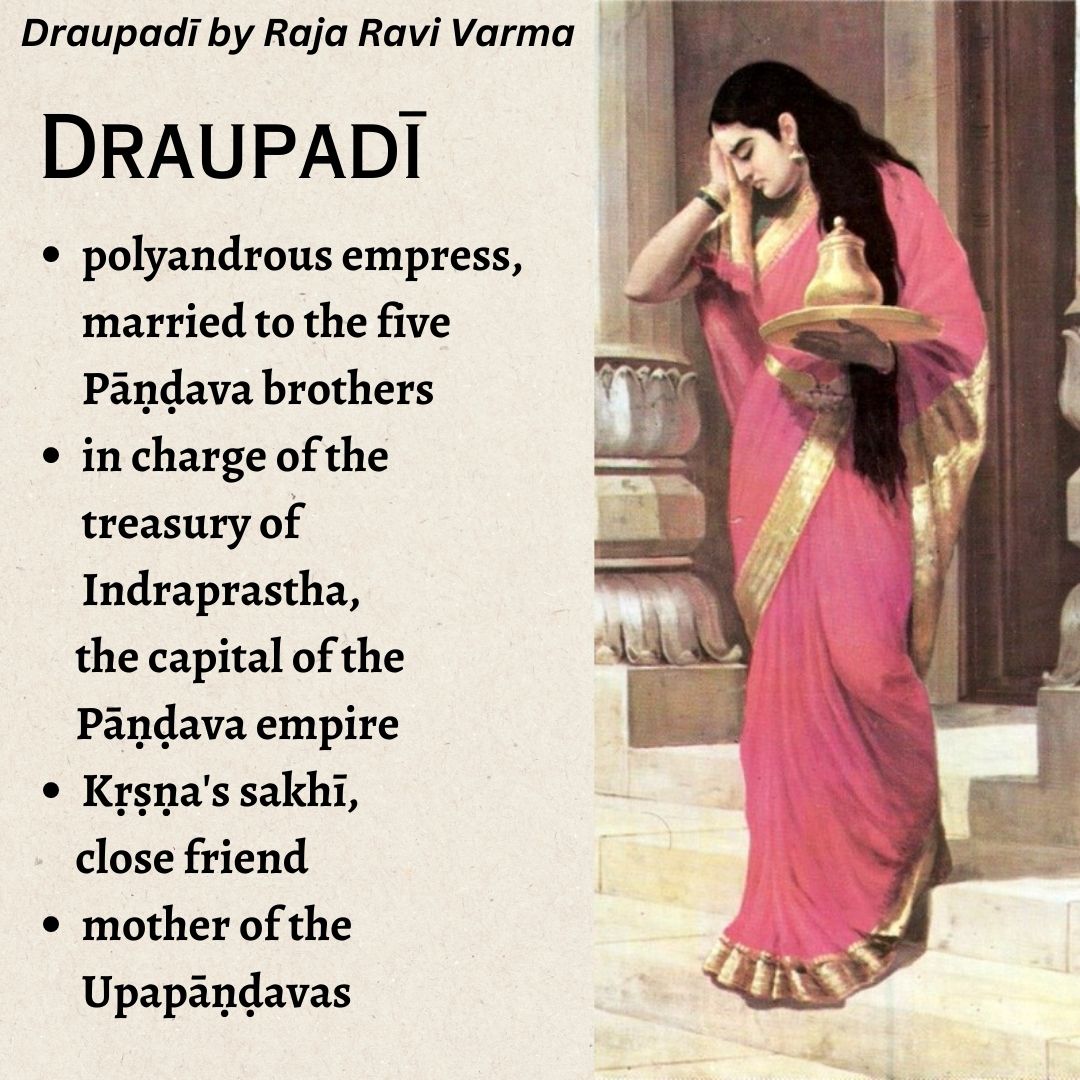

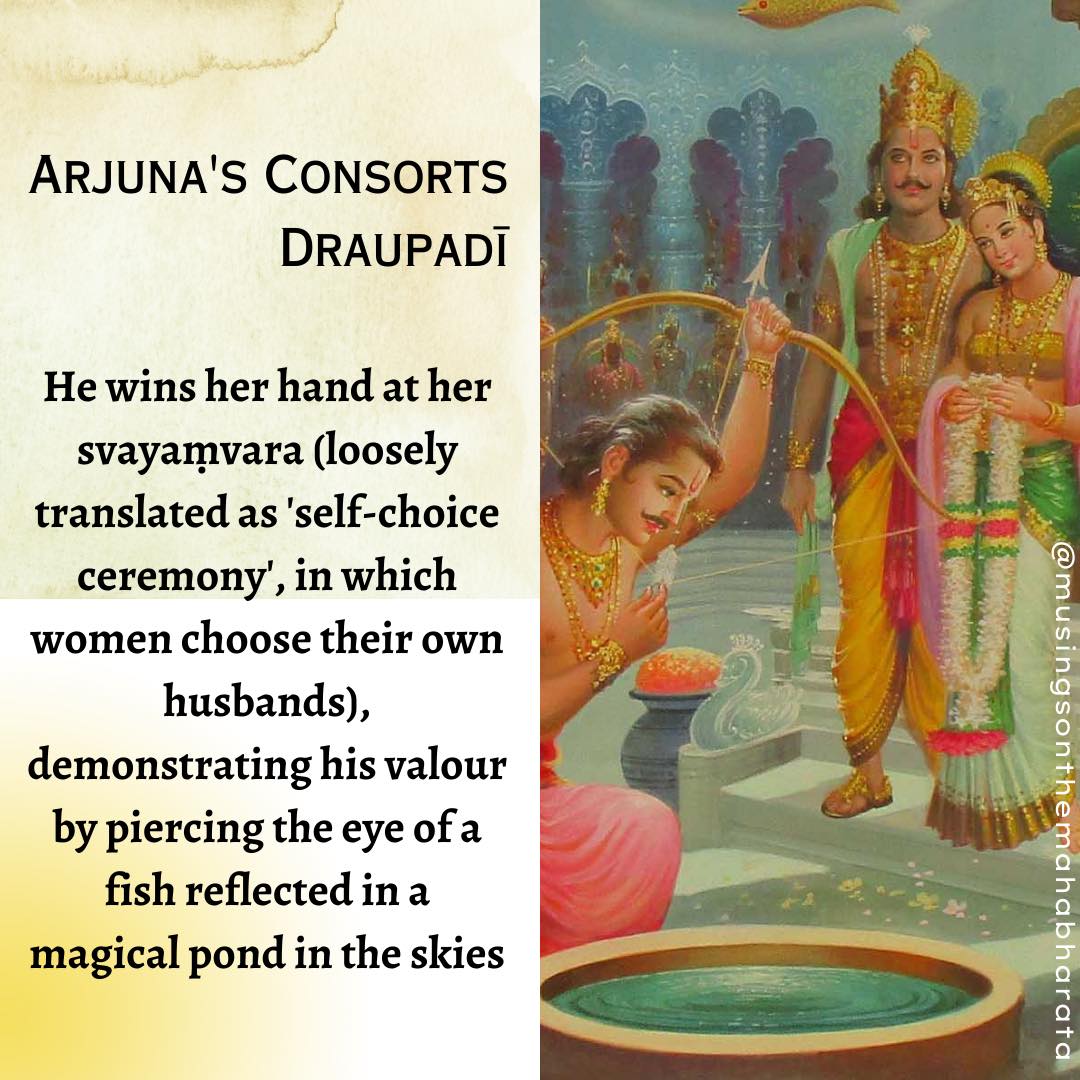

an argument several scholars have put forward is that the Mbh tells stories of men, and it has been written by men, for men. i would maintain that the first part of this claim can easily be deconstructed through the stories of incredibly empowered and empowering female characters such as Draupadī or Sulabhā.

although authorship of the Mbh has been indeed given to sage Vyāsa, the fluid nature of the epic, with many interpolations and changes made to its structure and with contributions which are anonymous in nature, has led scholars to claim that these changes were created by men, and, in this, the Mbh cannot properly encapsulate or express the female experience because women did not write it.

i will present a simple counterargument, emergent from discussions with Dr. Brian Black and my colleagues during a seminar at Lancaster University; more accurately, a question: how can we know this with certainty? how can we know that women did not contribute to the changes and interpolations that emerged in this epic?

i personally find it quite reductionistic and simplistic to automatically assume that women did not write these stories, or contribute to, for example, the creation of Draupadī’s narrative arc; i think this is exactly an assumption that could be misogynistic in itself, one stemming from a projection of women’s silence, namely to assume that such a great epic, which has shaped and moulded the culture in south asia, has not had any female contribution.

i would ask, why is this the automatic assumption that we make? 😊

listen to me speak more on these two subjects on my TikTok or on my IG account dedicated to my research: @musingsonthemahabharata.