amaryllis (/ˌæməˈrɪlɪs/[1]) – bears the name of the shepherdess in virgil's pastoral eclogues. it stems from the greek ἀμαρύσσω (amarysso), meaning "to sparkle", and it is rooted in "amarella" for the bitterness of the bulb. the common name, "naked lady", comes from the plant's pattern of flowering that blooms when the foliage dies. in the victorian language of flowers, it means "radiant beauty".

I have been asked on Tumblr how the Mahābhārata answers to the question of suffering (is suffering important? why? how?). First, this is an amazing question which hadn’t occurred to me to ask myself in relation to the Mbh, so I’m grateful for this prompt.

Second, I wouldn’t say that the Mahābhārata distinguishes suffering as important, but it does establish that it exists. All its characters undergo extreme suffering: from sexual assault to losing and grieving children, beloveds, friends, subjects. No character is spared from grief, and, in this, suffering is established as an inevitable reality of the human experience.

However, as scholar Emily Hudson argues in her book “Disorienting Dharma: Ethics and the Aesthetics of Suffering in the Mahābhārata”, there is another dimension the epic offers to the question of suffering, which is that of confronting it. Confronting suffering “involves cultivating a clear sense of the factors that contribute to human misery” (p.33) which the epic, I join Hudson in maintaining, equates with “the quality of one’s mind (manas)” or “intelligence (buddhi)”.

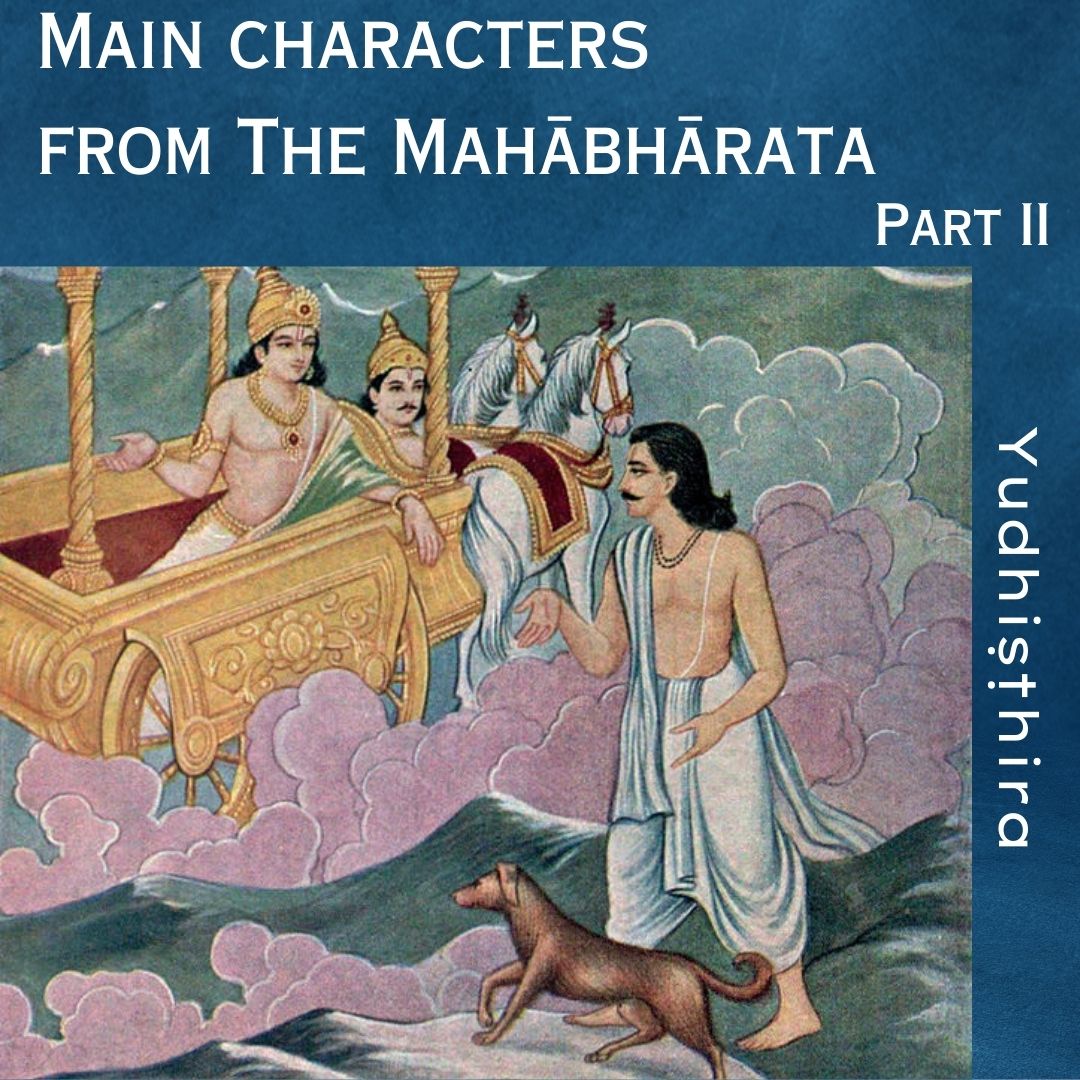

In a significant scene that occurs in the aftermath of the war, Yudhiṣṭhira, crippled by guilt and loss, refuses to rule, and wishes to renounce the world and his responsibilities in an effort to both punish himself and escape his pain. Kṛṣṇa, Draupadī and the other four Pāṇḍavas each give individual speeches to Yudhiṣṭhira in which they attempt to convince him that he cannot do so, that he has a duty to uphold, and, most fascinatingly, that the intensity of his suffering is derived from a misunderstanding of reality.

Most beautifully, Yudhiṣṭhira is told by Kṛṣṇa and Bhīma that “the battle he now must wage is the one with his mind (manas)” and he is to accept the impermanence of existence (Hudson, p.33; Mbh; 12.16.21-25; 14.12.1-14).

My understanding of this exchange is that, suffering will come. However, the extent to which we suffer is dictated by the clarity of our perception. One will naturally grieve death and loss and experience sorrow; however, the narratives we create around these emotions or experiences will dictate whether we remain stuck in them, or whether we welcome them as transitory states that experience themselves through us.

Just as Yudhiṣṭhira falls to his grief, yet picks himself up and rules, so can we.

Many thanks again to the Tumblr user from London who asked this question – if anyone has any other question, please, all are welcome here! Receiving questions from different perspectives is helping me see the epic in new ways in which my mind might not take me on. ![]()

Painting: The Destruction of the Yādavas. Unknown artist – do let me know if you know the artist!

*Note, a more accurate translation is:

BG: 11:32; trans. Eknath Easwaran.

Sometime ago, I was involved in a discussion about whether it was blasphemous for Oppenheimer to have quoted from the Bhagavadgītā upon seeing the explosion triggered by the atomic bomb he constructed. I was of the opinion that it was not. The opposing view was that Kṛṣṇa’s demolition was one of divine nature, whereas Oppenheimer’s manmade atomic bomb was not. Whereas, in this perspective, Kṛṣṇa’s violence and destruction were justified through Kṛṣṇa’s inherent divinity, Oppenheimer’s humanness disfigured his destruction with greed and impunity.

This comment rested at the back of my mind while I watched Oppenheimer the other night, and the film solidified my view.

I would maintain that, to one adhering to a non-dual outlook, there is no separation between Kṛṣṇa’s violence in the Bhagavadgītā (or, more accurately, in the Mahābhārata) and Oppenheimer’s manmade, humane violence. Violence is violence, and divinity (or Consciousness) is inherent in the fabric of that, as it is in all that is. The genius of Oppenheimer’s brain which created such a formidable and terrible invention functions on the same patterns that enable and are Kṛṣṇa’s destruction. There is nothing more inherently divine in death by astras (supranatural weapons controlled and imbued by mantras central to the Kurukṣetra war) than death by atomic bomb.

Not only do I argue that it was not blasphemous for Oppenheimer to quote the BG and internalise his work through its prism (and, incidentally, is blasphemy anything but a dual social construct? Can Consciousness be blasphemous of itself?), but I argue that this is exactly how the Bhagavadgītā is lived in direct experience. The Bhagavadgītā and the Mahābhārata are not lifeless ancient texts that are only accessible or relevant in an esoteric, abstract realm. The BG and the Mbh are lived here and now, from a moment to moment unfolding. I would maintain that we cannot pick and choose what we like from these texts or what aligns to our morals (such as teachings on goodness) and disregard the rest — or take it metaphorically. The last parvas of the Mbh are incredibly violent and include gory descriptions of war, and the BG occurs on the battlefield of said war. This, in my view, does not signify that the texts glorify violence — no more than they glorify any other aspect of creation. It is a sign that violence exists as a natural development of the triadic cycle of creation (creation — preservation — destruction), and it is a manifestation of Consciousness.

The Bhagavadgītā coming alive to Oppenheimer upon witnessing his own potential for destruction is a testament to the BG’s existence in the collective consciousness as an expression of truth, pulsing and flowering for the one who expands their individual consciousness enough to tap into it and to allow it to manifest through themselves.

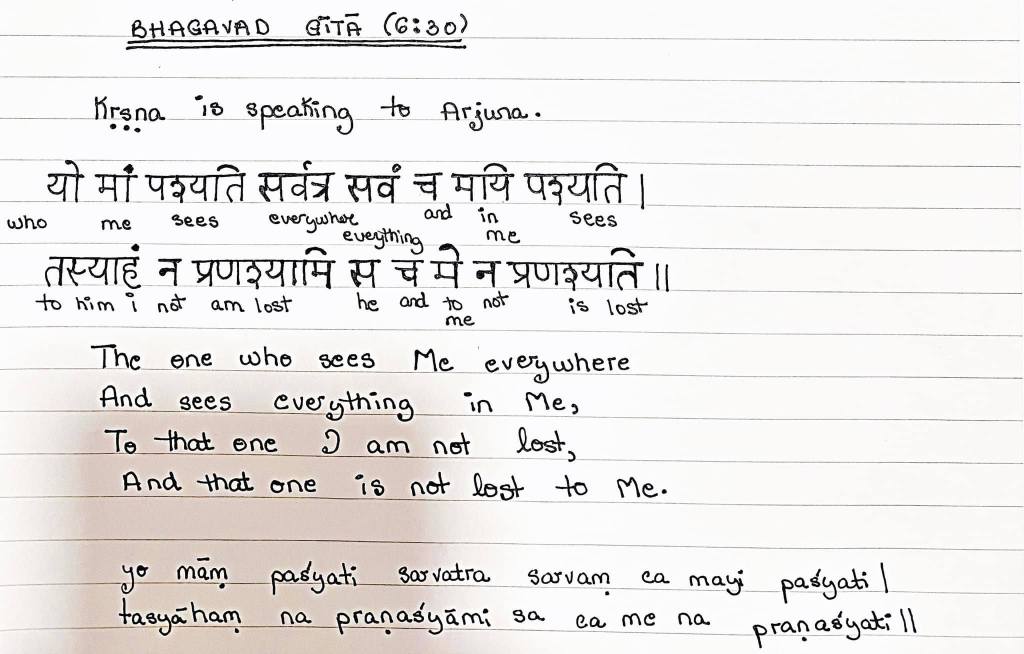

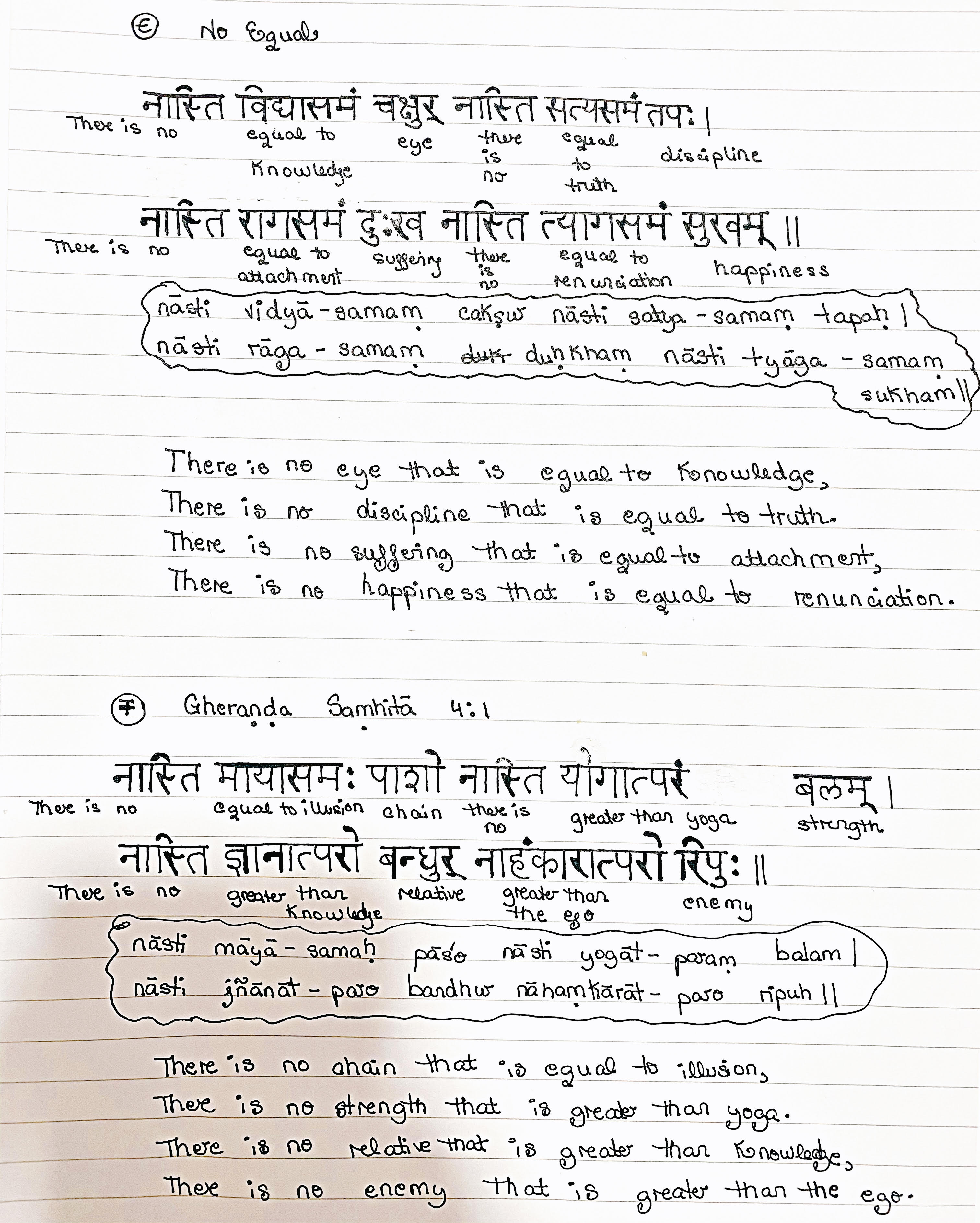

after a fruitful opening term completed with a first class honours, i’m excited to proceed with my study of sanskrit at the oxford centre for hindu studies! translations guided by the brilliant zoë slatoff-ponté. ♥️

happy Vijayadaśamī! ![]() from this month’s newsletter of Śabda Institute. honoured that my poem accompanies the announcement of such an exquisite offering

from this month’s newsletter of Śabda Institute. honoured that my poem accompanies the announcement of such an exquisite offering ![]() in this highly auspicious time, may our longing fuel our sādhanā, and may our devotion sweeten its unfolding.

in this highly auspicious time, may our longing fuel our sādhanā, and may our devotion sweeten its unfolding. ![]()

Dear One,

The Śabda Saṅgha is continuing its study of the Bhagavad Gītā with a new theme – that of Bhakti Yoga. In honour of this new cycle of study, we are pleased to share a beautiful poem of longing and devotion by one of Kavithaji’s students, Téa Nicolae.

thirst

infused with devotion

my days unfurl tenderly

chinks fissure the armour plate of the self

and life dances through the cracks

madly enamoured

i long for the Beloved’s caress

my throat, so swollen

my mouth, so parched

my Beloved quenches the thirst:

grace pours down in ripples

i drink hastily

and, journal-musing: this term has been so fruitful, despite working completely from home! i haven’t spent so much time at home since high school and, to an extent, i’ve felt like i was transported back to that time – minus the insecurities ![]() !

!

anyway, Mahābhārata’s been living in my head rent-free, and i’ve dedicated my time & research to writing about violence & religious conflict as they transpire in my beloved Kṛṣṇa’s actions and speech in the Kurukṣetra war & in the Bhagavad-gītā. ![]() additionally, i’m excited to be completing my first independent study, an exploration of issues of purity & impurity in non-dual philosophy, and to be undertaking a small research project into consumer spirituality and the relentless commodification that comes with it.

additionally, i’m excited to be completing my first independent study, an exploration of issues of purity & impurity in non-dual philosophy, and to be undertaking a small research project into consumer spirituality and the relentless commodification that comes with it. ![]()

all in all, i am deeply grateful to be offered the opportunity to explore the marvellous Mahābhārata once more. its poetic teachings and ample cosmological symbolism have permeated through me and i often wish its universe would swallow me whole ![]() nonetheless, i’m certain that one needs to dedicate ten lifetimes to one parva, and i am not exaggerating ! as Vyāsa himself states in Ādi Parva: ~ what is found here, may be found elsewhere. what is not found here, will not be found elsewhere ~

nonetheless, i’m certain that one needs to dedicate ten lifetimes to one parva, and i am not exaggerating ! as Vyāsa himself states in Ādi Parva: ~ what is found here, may be found elsewhere. what is not found here, will not be found elsewhere ~

i’ve never had so much workload crammed into such a short timespan, but i’ve been trying to savour the flavour of busyness. it’s alien to be doing all of this in my childhood home. it’s a fun parallel, though – whilst musing on the Bhagavad-gītā (by the way, we are exploring the B-g in our monthly satsaṅgs at #sabdainstitute with our beloved teacher Dr. Kavitha Chinnaiyan!), it dawned on me that i was so hungry for this knowledge in my teens, but i didn’t know where or how to look. it came to me in the end, and what a great joy it is ~ to sip the honey of “the stainless lotus of the Mahābhārata, born on the waters of the words of Vyāsa, fully blossomed through the grace of Hari…” ~ {my vague attempt at translating a śloka} ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

mid-term study-break selfie ![]()

so thrilled to share that i finished the two papers i’ve been working on these past months: “Feminine Dimensions of ‘God’: The Deification of Mahābhārata’s Tragic Heroine” & “The Western Revival of Goddess Worship”. ![]()

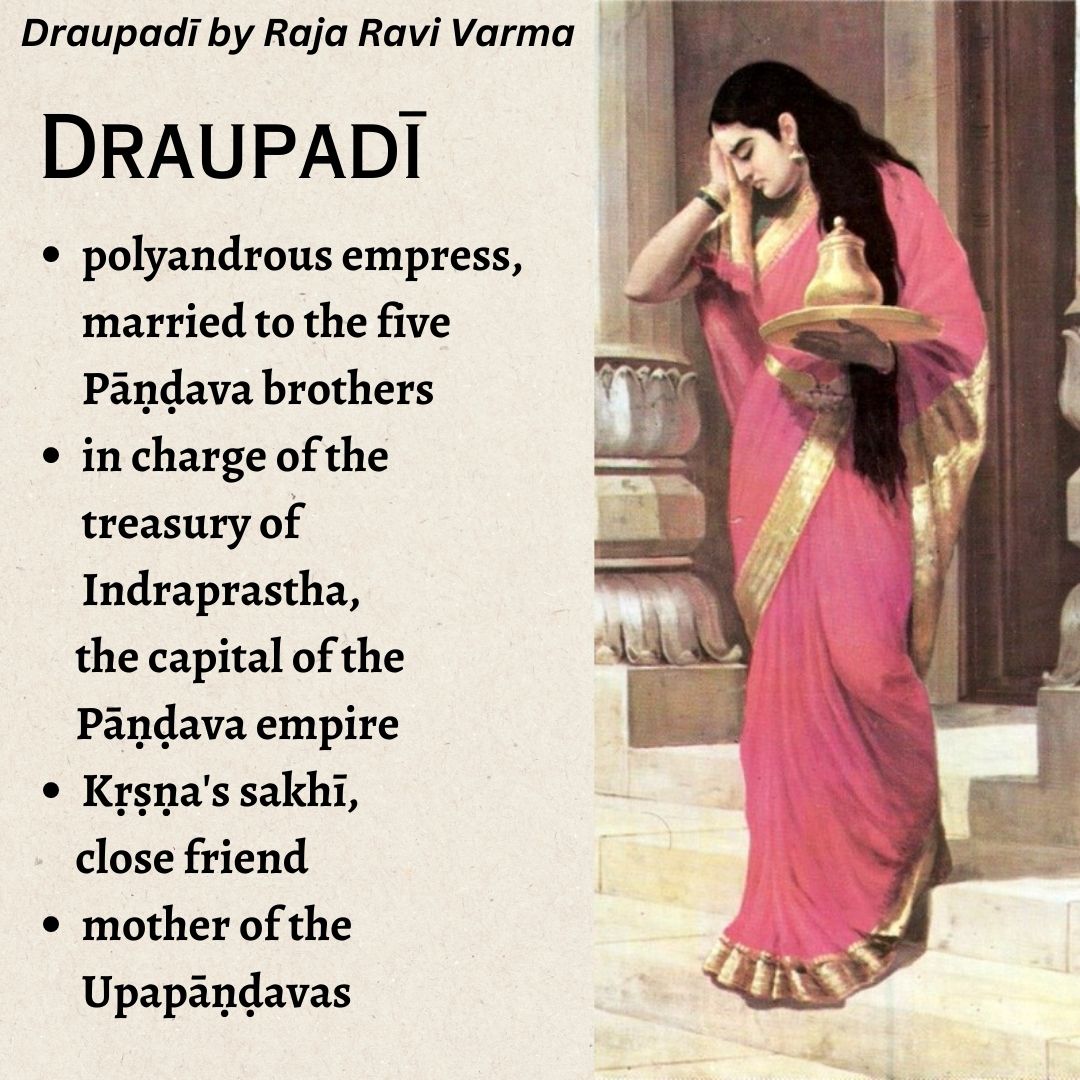

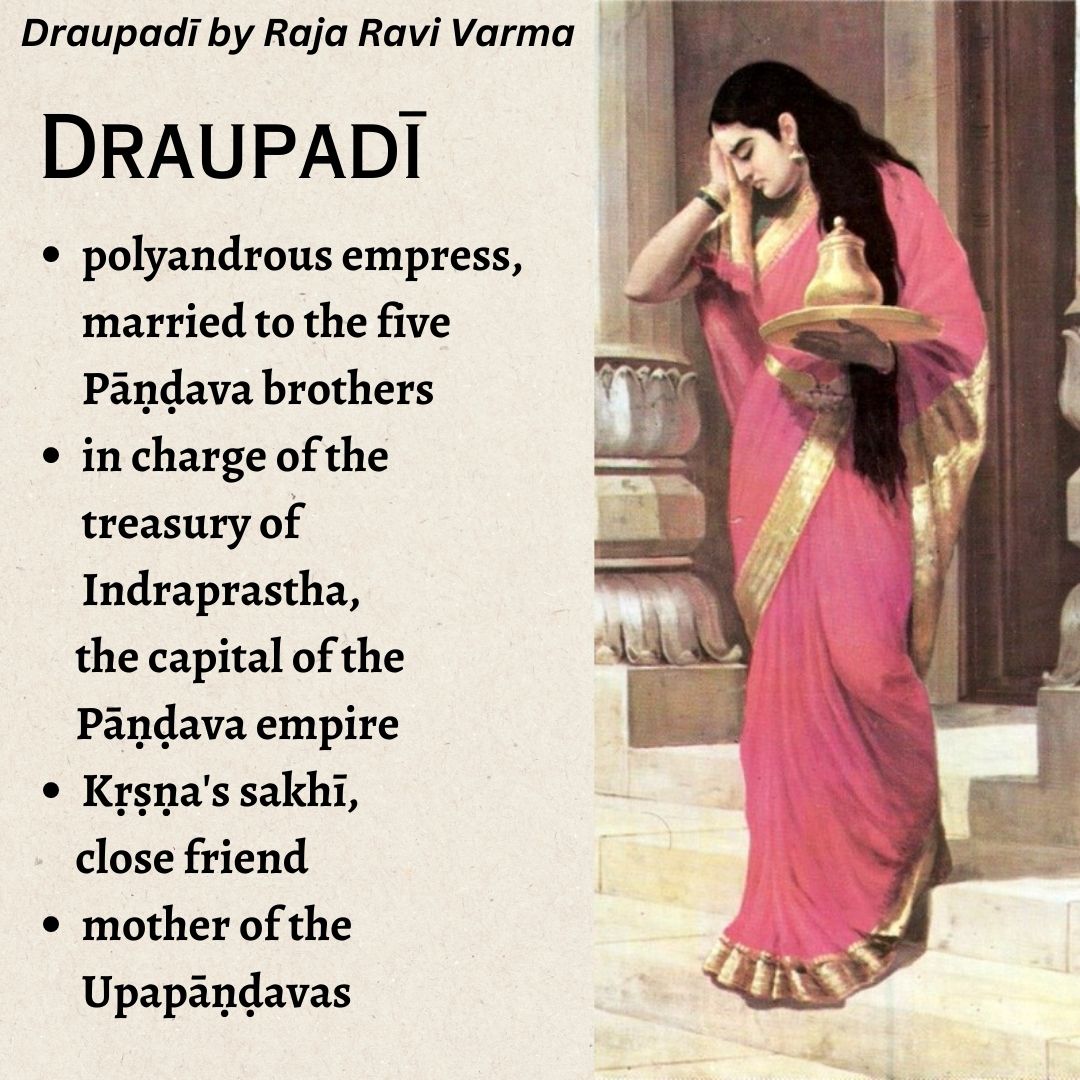

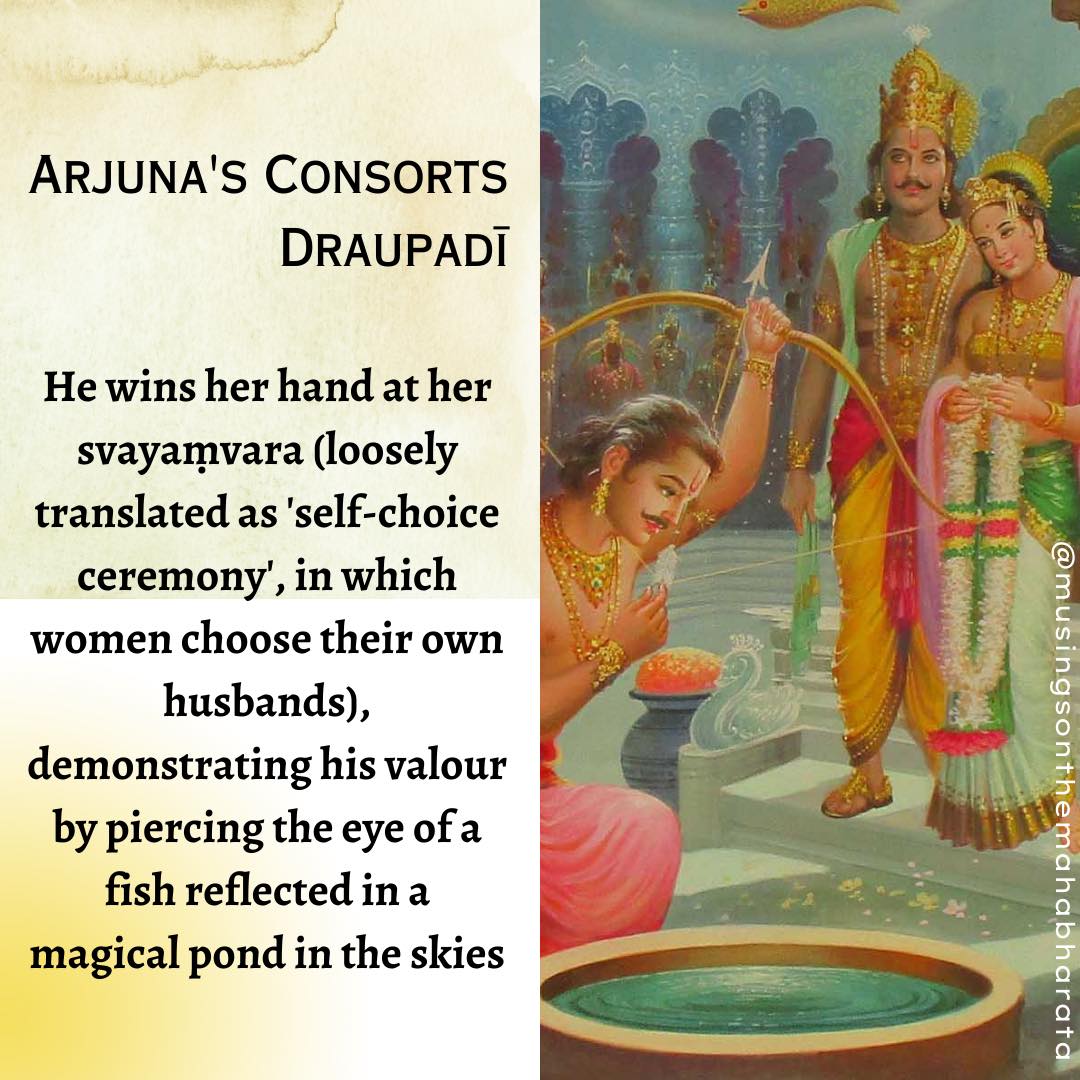

my first essay explored the richness of the non-dual concept of ‘God’ by addressing the intricate worship of Draupadī, Mahābhārata’s enigmatic female character – whose tragic and distinct storyline establishes her as a multifaceted heroine: a devoted wife; a caring mother; an abused and vindicative woman; a polyandrous empress; an avatar of the Goddess; the Supreme Parāśakti, the all-pervading absolute reality herself; the celestial Śrī. i argued that, through the worship of an abused & vengeful woman, her devotees are deifying the entirety of the human experience. ![]() my second essay employed a discourse rooted in psychoanalysis, and was centred on the therapeutic values Goddess archetypes hold for the traumatised female psyche + commented on the ramifications of the phenomenon of religious revival in a secular age.

my second essay employed a discourse rooted in psychoanalysis, and was centred on the therapeutic values Goddess archetypes hold for the traumatised female psyche + commented on the ramifications of the phenomenon of religious revival in a secular age.

![]() i have adored writing both, no matter how frustrating the writing inevitably got at times. i had so much fun with the two topics, which i’m very passionate about, but i especially enjoyed delving into Mahābhārata – three months in, and i still am absolutely fascinated by it and in awe of the beautiful Draupadī, who i’m sure will be the subject of much of my future research.

i have adored writing both, no matter how frustrating the writing inevitably got at times. i had so much fun with the two topics, which i’m very passionate about, but i especially enjoyed delving into Mahābhārata – three months in, and i still am absolutely fascinated by it and in awe of the beautiful Draupadī, who i’m sure will be the subject of much of my future research. ![]()

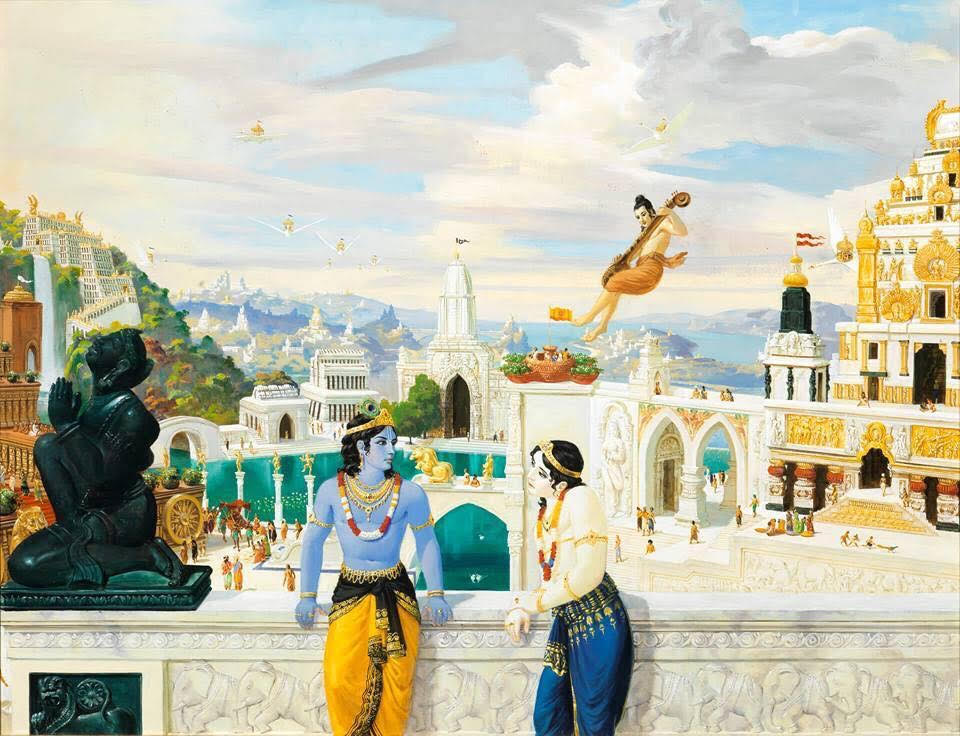

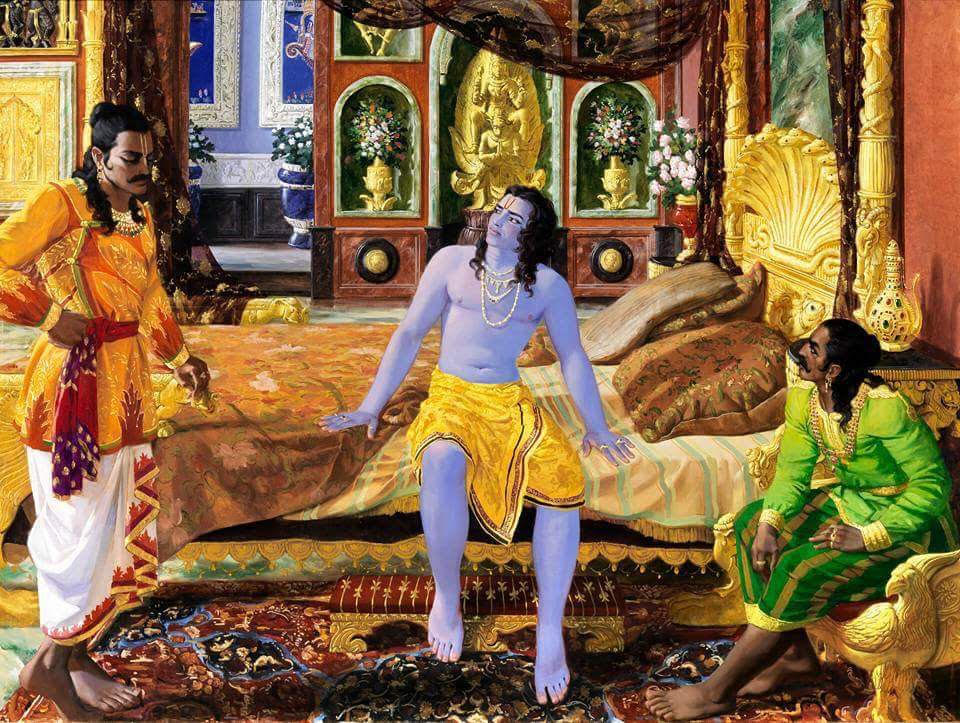

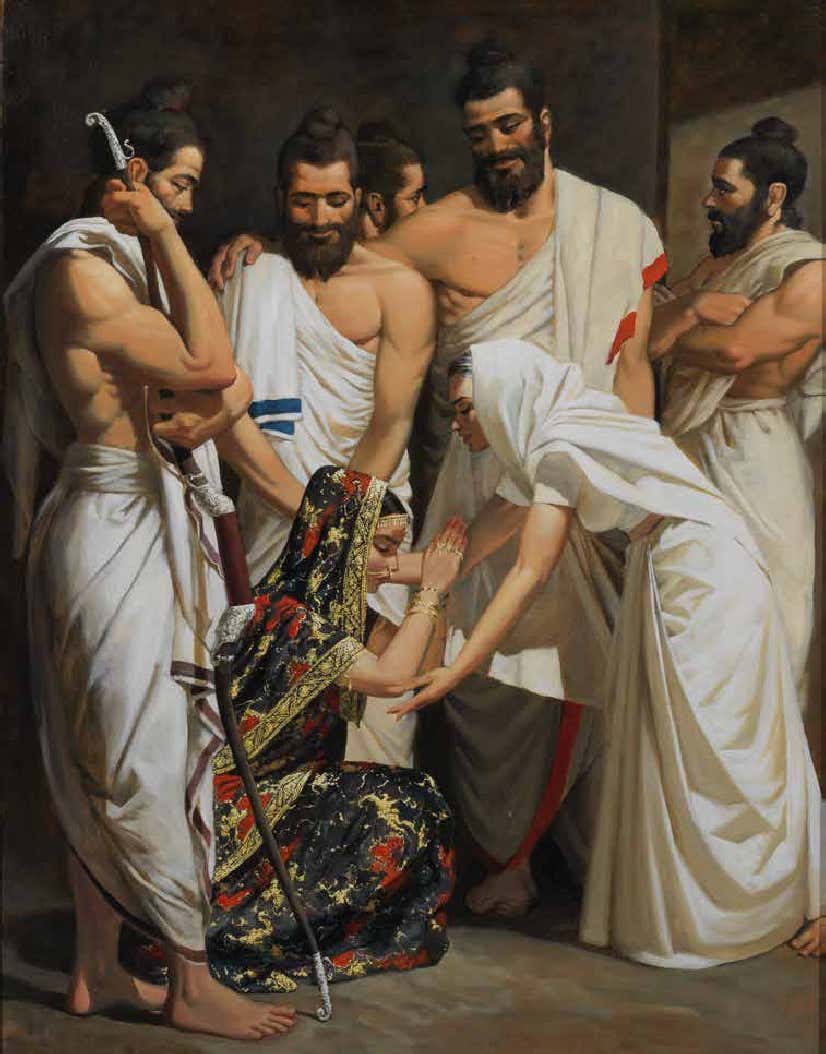

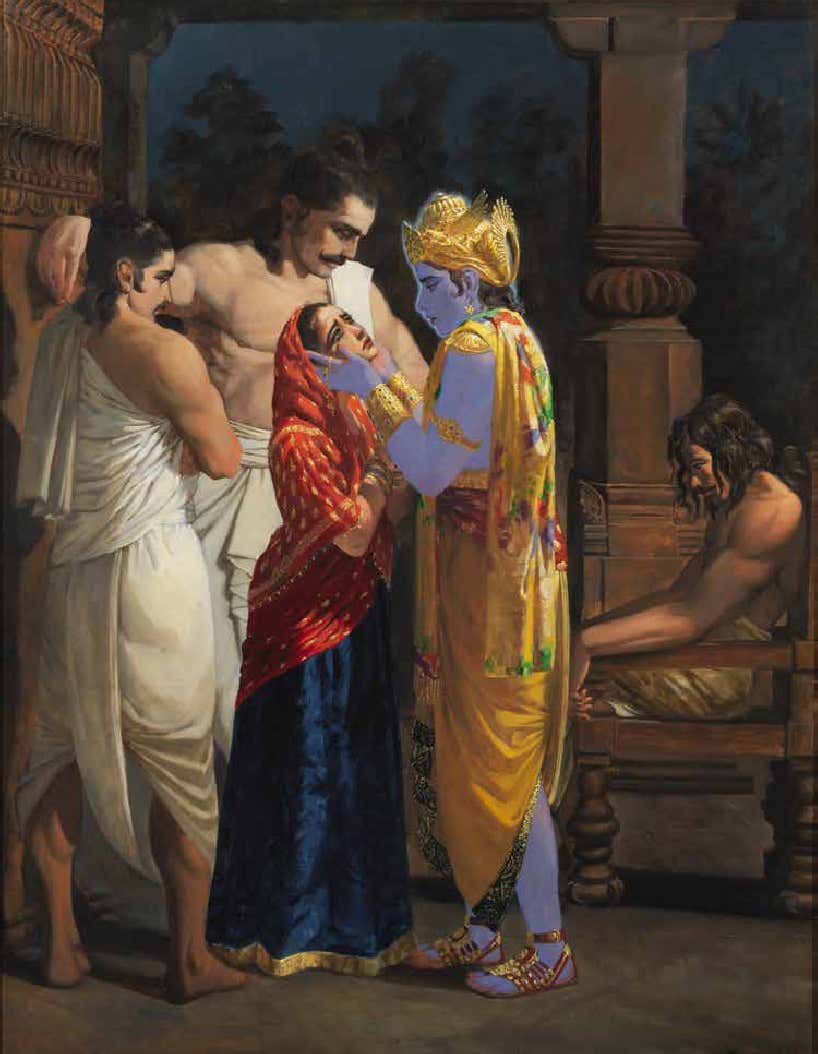

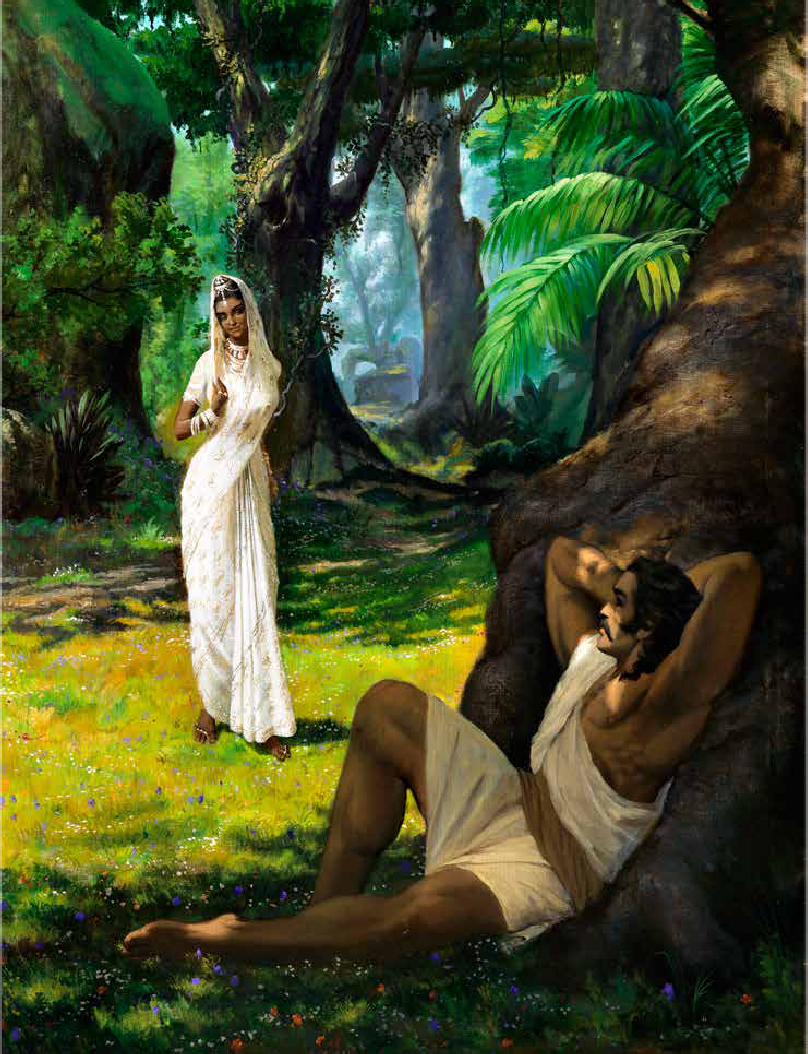

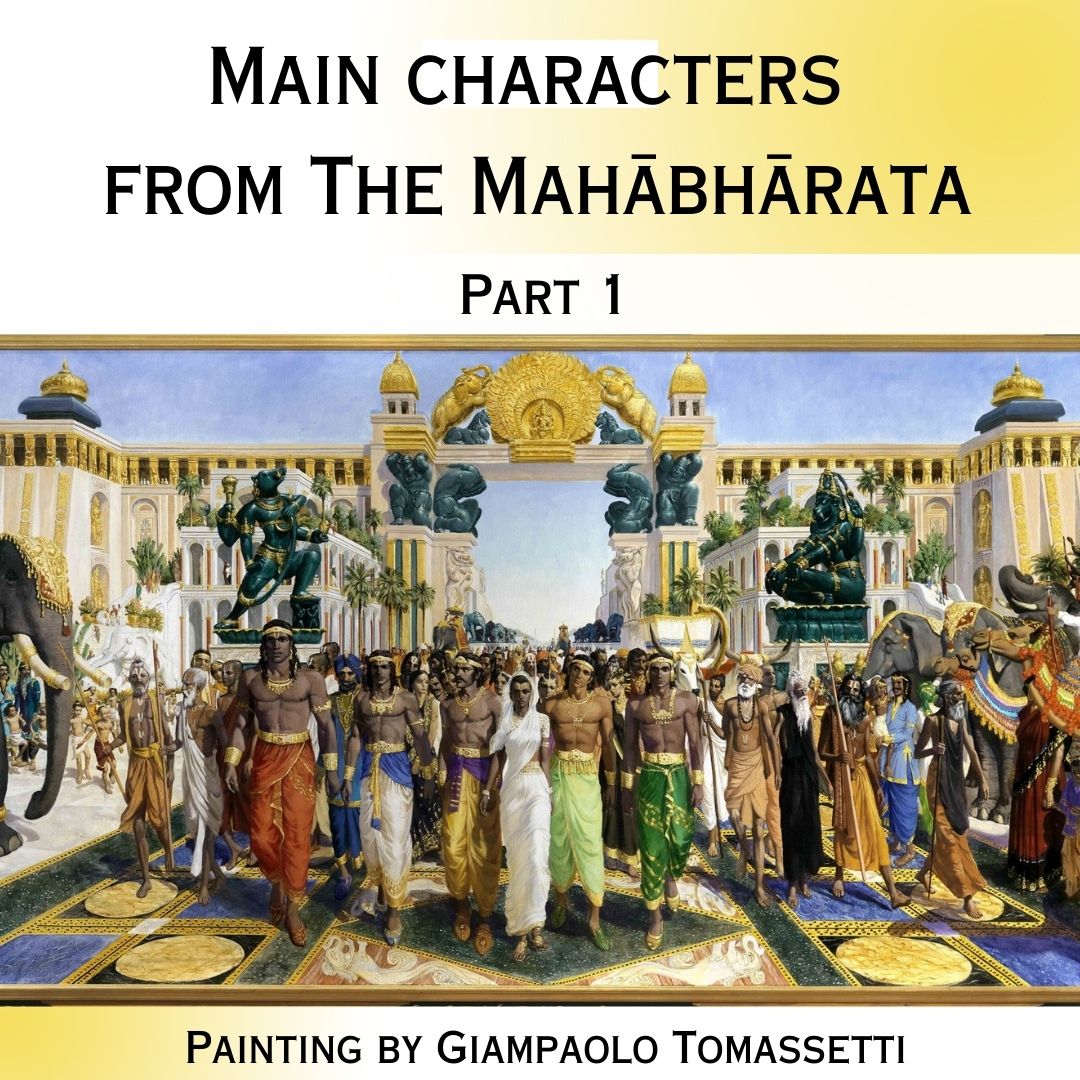

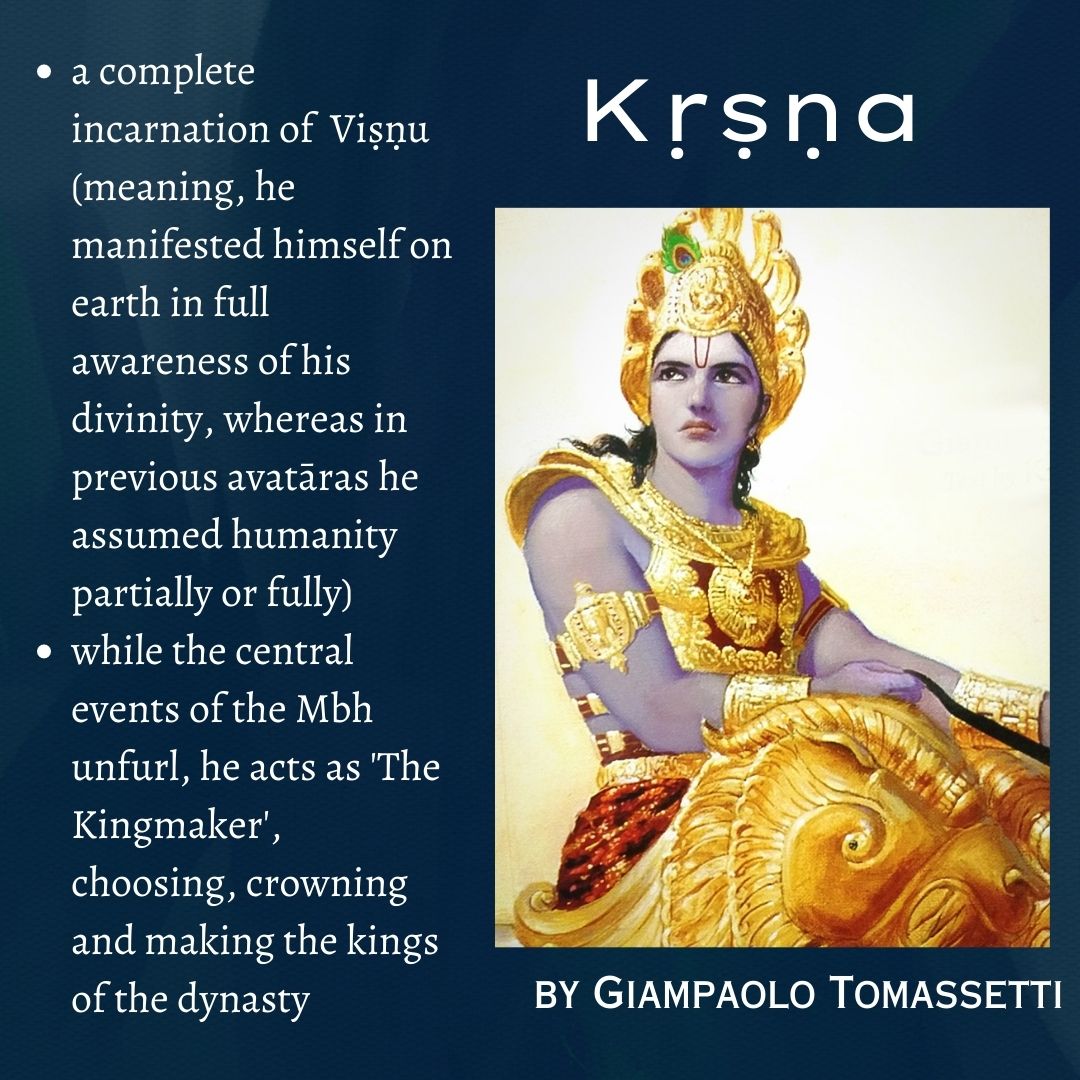

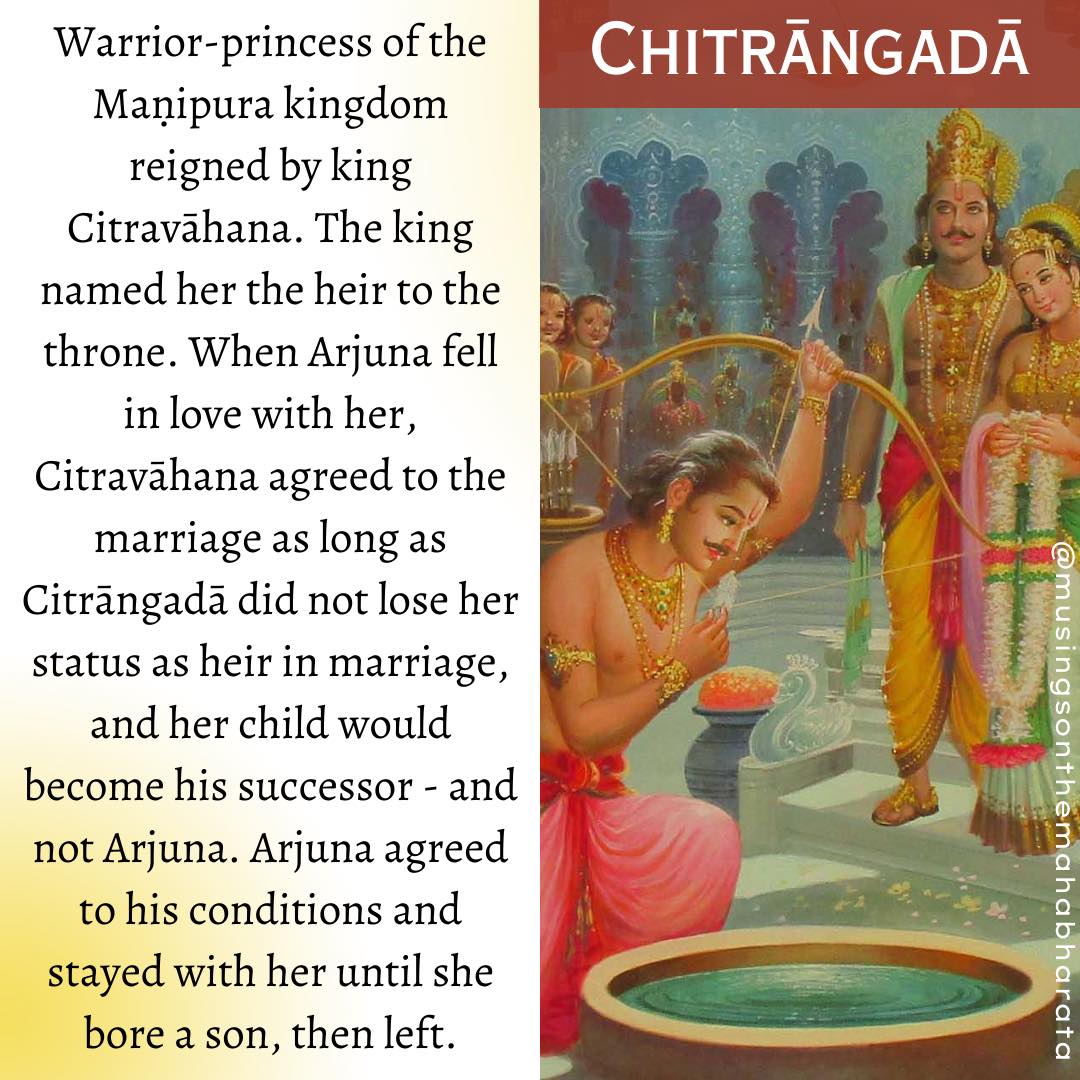

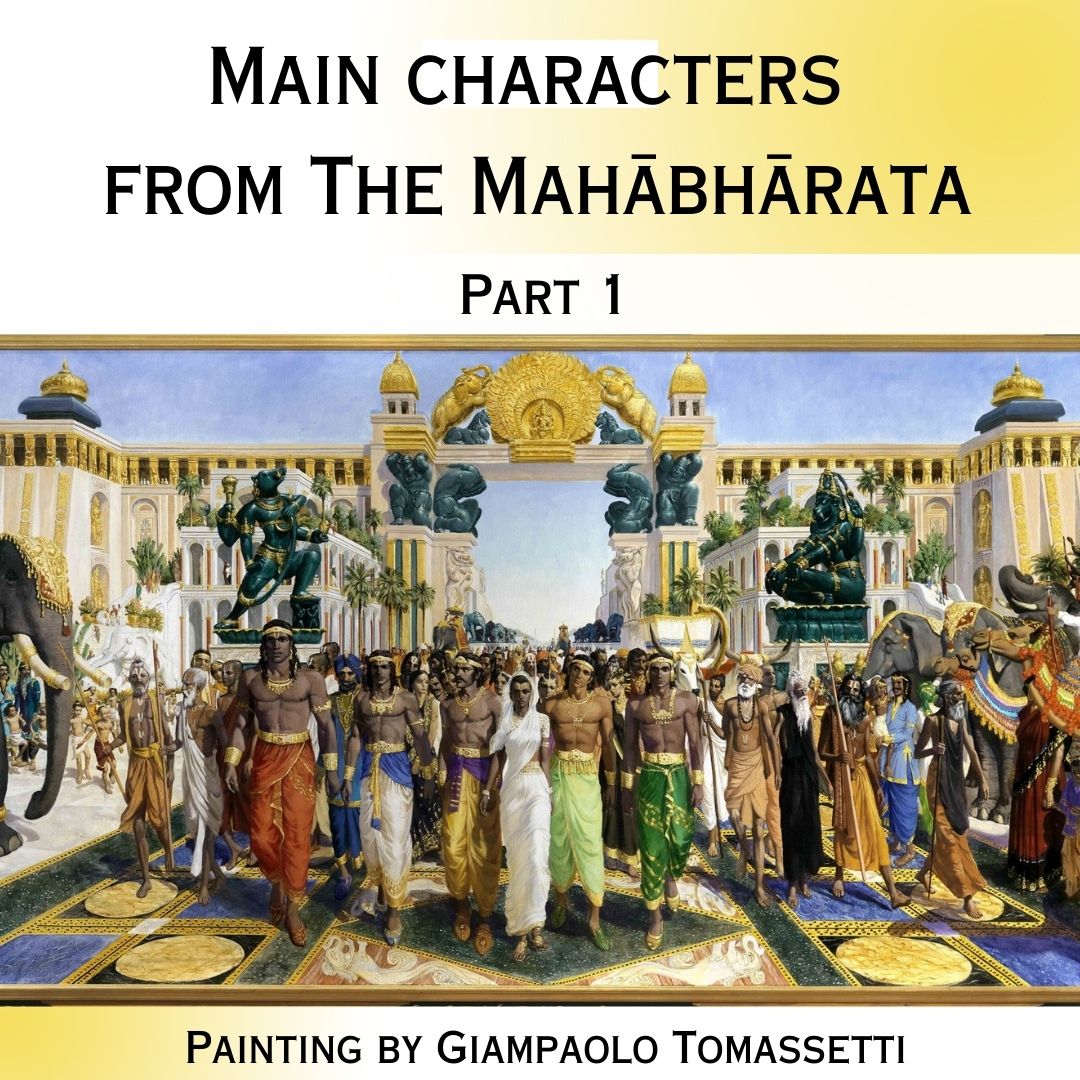

on this occasion, attaching here the marvellous paintings of Giampaolo Tomassetti, who dedicated 17 years of his life to studying & painting the Mahābhārata ![]() pictured:

pictured:

Kṛṣṇa & Balarāma in Dvārakā (my favourite ![]() )

)

Kṛṣṇa advising the Pāṇḍavas

Draupadī meets Kuntī

Kuntī & Karṇa

Kṛṣṇa comforting Draupadī after ~ dice match & disrobing ~

Kṛṣṇa reveals his universal form (Govindarūpiṇī)

Kuntī & Sūrya

Kṛṣṇa, the Pāṇḍavas, Draupadī & Kuntī in Indraprastha

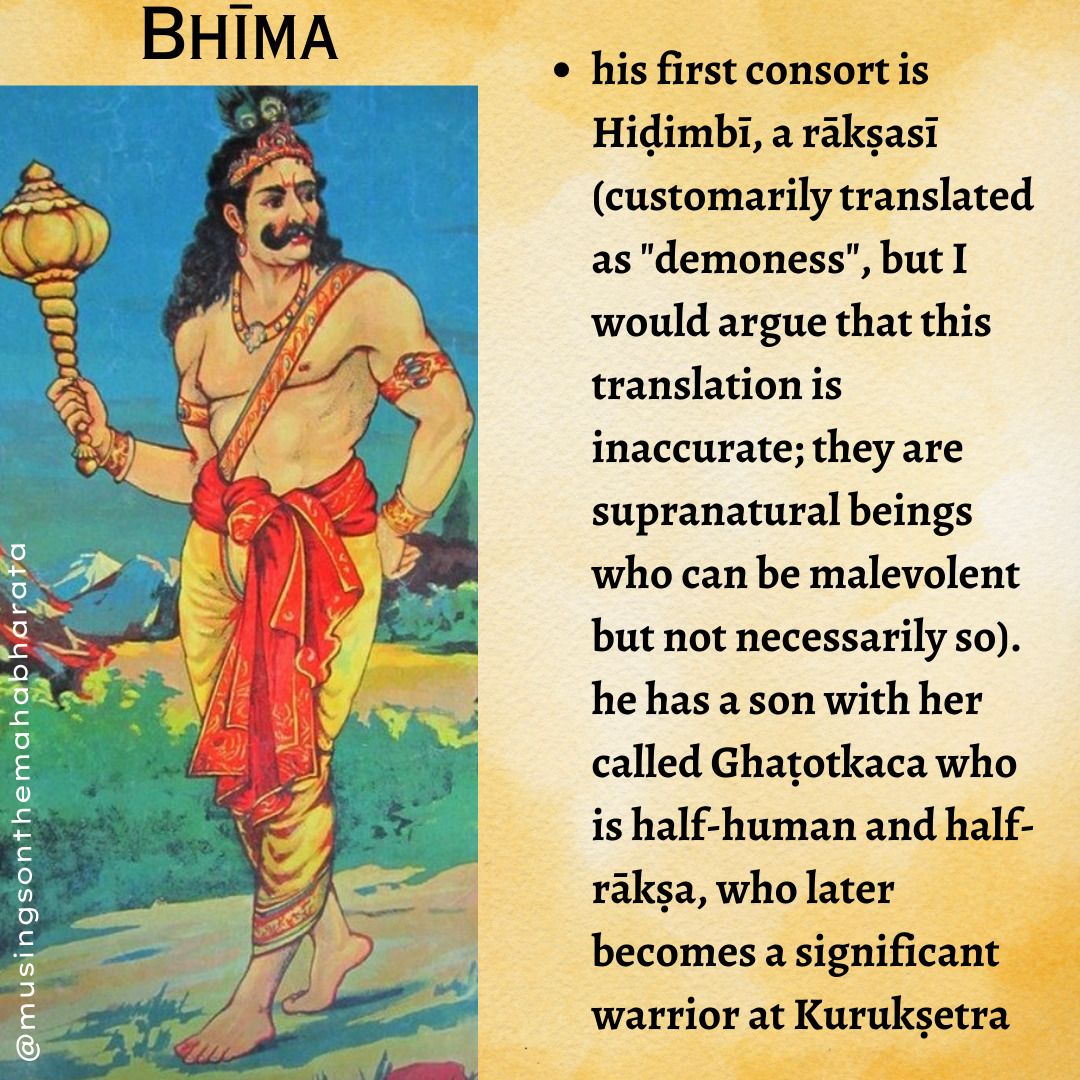

Bhīma & Hiḍimbī

Dvārakā