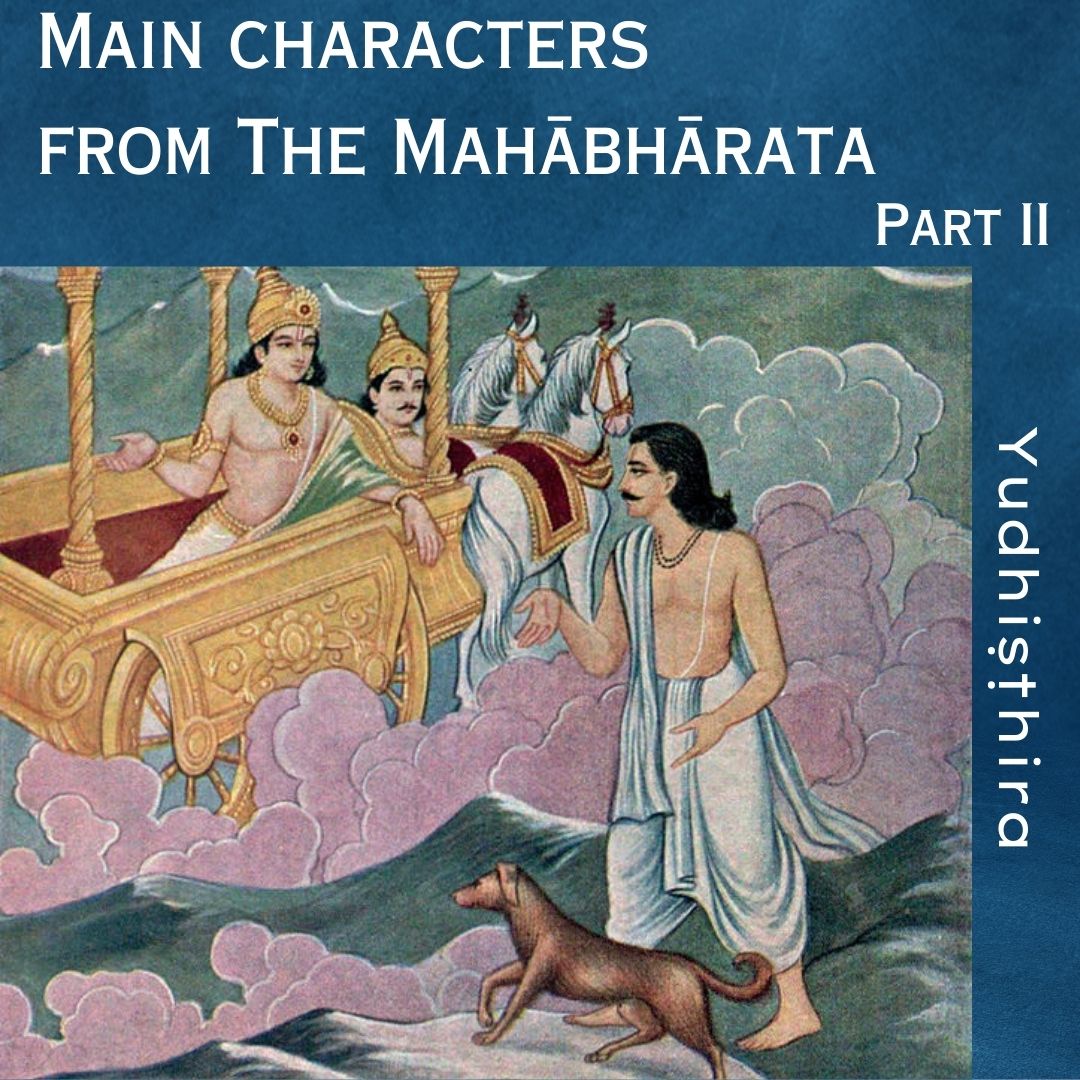

The order of the stakes of the dice game in the Mahābhārata goes as follows:

1) Yudhiṣṭhira stakes and loses the Pāṇḍavas’ wealth, army, empire, throne, weapons

2) Yudhiṣṭhira stakes and loses the autonomy of his four younger brothers, and they are enslaved on the spot (and they submit to it)

3) Yudhiṣṭhira stakes and loses his own autonomy, rendering himself enslaved (and submitting to it himself)

4) lastly, Yudhiṣṭhira stakes and loses Draupadī’s autonomy. The Kauravas roar in excitement, and they send a servant to fetch Draupadī to the sabhā (the royal hall) so she can be enslaved publicly.

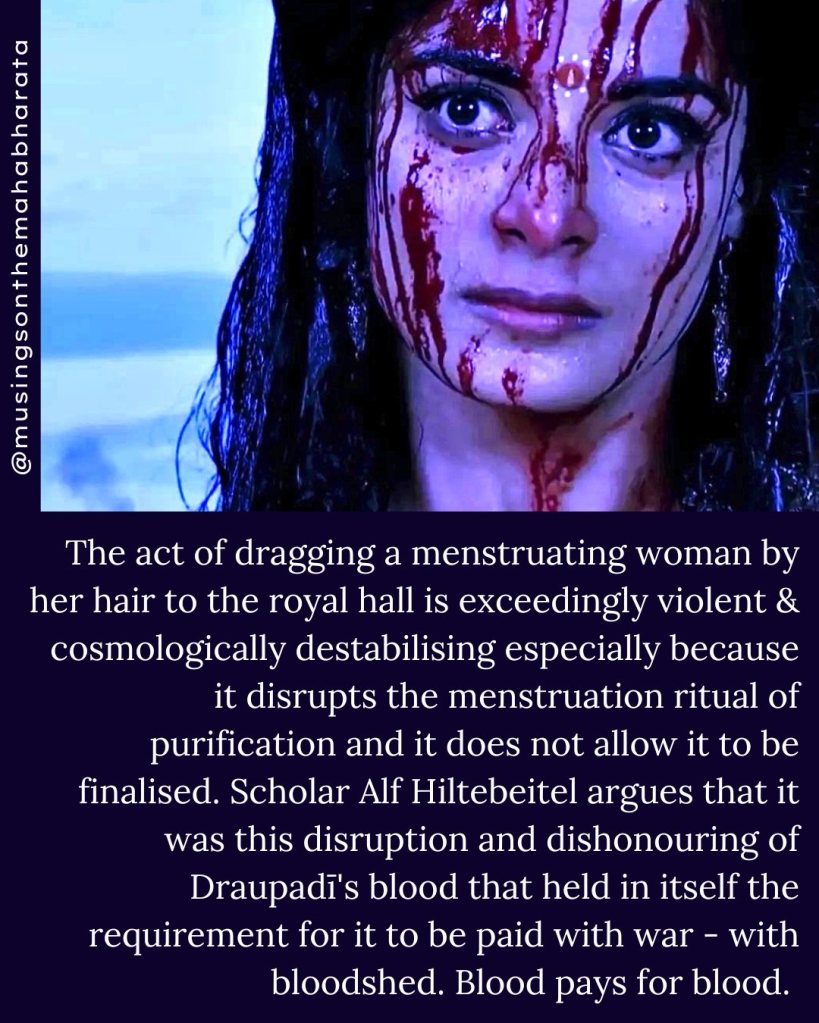

Draupadī is absent from the sabhā at the time the dice game unfolds, as she is in her private chambers, menstruating. The servant comes to her and announces the outcome of the dice game. She is told that she has been ordered to present herself as a servant before the Kuru dynasty. She refuses to go, and says she wants one question to be asked to Yudhiṣṭhira:

“Did you first lose yourself, or me?” (2.60.9)

The servant returns to the sabhā and asks Draupadī’s question to Yudhiṣṭhira, who remains silent. The Kauravas become enraged by what they perceive to be Draupadī’s defiance, and one of them, Duḥśāsana, goes to fetch her himself. When she still refuses to come, he grabs her by her hair, drags her to the court and molests her publicly.

However, Draupadī is unbent: she delivers an incredibly powerful speech in which she continuously asserts her independence, challenges and rejects the men’s claims to her freedom, questions and denies the validity of the dice game, and, ultimately, overturns its verdict. In this speech, she presents a series of arguments, and I will analyse each in a series of upcoming posts.

Her first argument is her first question, which infers that, even if Yudhiṣṭhira did have any authority over her status (which she later challenges and denies as well), he lost all authority which could have been argued that he exerted over her the moment he renounced his independence. One who is not their own master cannot be the master of someone else, and one who is dependent cannot impair another’s independence.

My Mahābhārata blog: https://www.tumblr.com/musingsonthemahabharata

IG: @musingsonthemahabharata. ❤️🔥